By Paul Chatterton

This post originally appeared in Medium

Some reflections on how to build a safe, sustainable future

In this article I reflect on one of the defining issues of our age — how we move around our towns and cities in a way that can support wellbeing, reduce inequality, improve quality of life and the environment. I do this largely through my home city, Leeds, which like many places, finds itself in a transition between two transport ages: the car age of the motorway city, and the sustainability age of the active travel city.

Leeds eagerly embraced the modern era, building the UK’s first urban motorway, earning the reputation of ‘motorway city of the seventies’. Throughout the 1960s, city engineers and architects Charles Geoffrey Thirlwall and Edward Weston Stanley, as well as political leaders such as Frank Marshall, rolled out a comprehensive urban renewal plan that came to be known as ‘the Leeds Approach’. While this plan to its credit also focused on pedestrianisation, suburban centres and public transport, it was, in essence, a blueprint for perfecting a car based city. As it stated:

‘Because of…. the greater penetration and flexibility possible with public road transport the city has concluded that the development of this form of transport is more appropriate to conditions in Leeds than the extensive employment of local rail services or the provision of other forms of fixed mass transit facilities’.

The whole city was re-imagined through what was, for the period, a bold and visionary approach. It brought many freedoms, establishing the car as the most effective means of getting around. But, largely beyond the horizon of its creators, the plan stored up rather than solved many major problems over the ensuing decades – congestion, air quality, social inequality, physical disconnection, road casualities and carbon emissions.

Fast forward fifty years and an equally ambitious new ‘Leeds Approach’ is required, but in a very different direction — an approach to planning and transport that reverses Leeds out of the motorway city and into a safer, sustainable active travel future.

Many aspects of city life (institutions, infrastructures, behaviours and resources) need changing in order for this kind of new reality to emerge. The middle of a transition is a difficult place to be. It can be marked by confusion, conflict and competing priorities which pulls a locality, its local politics and residents, in multiple directions. Cycle lanes, wider pavements and low traffic neighbourhoods sit alongside new arterial retail parks, relief roads and car-based volume housing estates.

The key to managing a successful transition is for a city leadership team to purposefully set a new course with a clear vision and milestones to get there — and sell the benefits to its citizens, with resources and institutions to back this up. Below I offer some reflections on what Leeds is doing, the opportunities of moving away from the motorway city, and the broader push for active travel as part of the COVID recovery.

COVID recovery and active travel

Towns and cities across the world are making real efforts to rapidly lay down active travel (walking and cycling) infrastructure. This has been given recent momentum by COVID recovery transport plans. As public transport remains below full capacity due to social distancing, without a significant shift to active travel many car-reliant places could face imminent gridlock, as well as an acceleration of long standing problems of carbon emissions and air quality. We now also understand that long term exposure to transport-related air pollution can reduce lung function and lead to higher COVID cases. Switching from cars to active travel is no longer just a quality of life issue; it’s also a life saving one.

Given this context, in May 2020, the UK Government launched an emergency travel fund to promote active travel as part of its COVID recovery plans. It has made funding available to English local authorities in two separate phases to quickly bring forward their plans for active travel. The sums are modest given the scale of the task but the ambition and innovation is potentially high. To secure funding cities and towns have to evidence closing roads to motorised vehicles, and reallocating road space for walking and cycling.

Why active travel?

Let’s just recap on the broader challenges, and the reasons we need a shift. Active travel means getting about in a way that makes you physically active, like walking or cycling, but of course it also includes other means such as e-bikes, scooters and wheelchairs. It usually means short journeys, like walking to the shops or local school, cycling to work or to see friends and family, or cycling to the train station. 70% of all journeys in the UK are less than five miles. But for distances of between one and two miles, over 60% of journeys are still made by motor vehicles. So, the possibilities for converting journeys to active travel, especially e-bikes, are huge.

There’s also a compelling evidence base for shifting away from motorised vehicles to active travel. Here’s some figures from my home city, Leeds, which is currently the largest city in Europe without a mass transit system, and is highlighted as having some of the most unsafe air quality in the UK. Vehicles are the biggest source of outdoor air pollution in Leeds. When fewer people drive, air quality improves. Because of lighter traffic, outdoor nitrogen dioxide levels are up to 40% lower at the weekend.

According to analyis by Leeds’ public health team, between 2017–25, reducing people’s exposure to nitrogen dioxide and PM2.5 (the two major air pollutants) would result in an estimated 750 fewer deaths amongst those suffering from chronic conditions such as coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), stroke, asthma, diabetes and lung cancer. Reducing its high pollution levels would save Leeds based NHS and social care up to £36 million between these same dates. Moreover, 337 people were killed or seriously injured on roads in 2018, and transport accounts for 43% of city carbon emissions. On top of all this, a typical vehicle driver loses forty hours per year stuck in traffic, although it is hoped changing commuting patterns post-COVID will change this.

Encouraging more active travel is an obvious priority for towns and cities as it tackles this basket of problems; and it brings immediate benefits — improved public health from more physical activity and better air quality, increased road safety especially for children and those on foot, bike and wheelchair, improved local quality of life through more physical interaction, and reduced carbon emissions. If it goes hand in hand with good planning and design, it can also offer the quickest and cheapest journey times for the majority of trips we make.

So, what’s happening in Leeds?

Leeds City Council has a long-standing ambition and programme of work to promote active travel, through CityConnect and Connecting Leeds. Since lockdown this has been given new momentum. The municipality started to use the Common Place interactive platform to gather ideas on active travel improvements across the city. The Create Streets social enterprise also created a similar map which informed the wider council led consultation.

Since May, I have been part of a new group supporting and informing the introduction of emergency active travel infrastructure in Leeds. The focus of this group has been the Government’s Emergency Travel Fund, to which Leeds, like other UK local authorities, has applied to support its Connecting Leeds COVID-19 Transport Response. There have been four action areas, all of which offer important learning in this broader transition to an active travel city.

The first is the School Streets Programme, closing selected roads around schools to create safe places, which is especially important now so schools can operate social distancing. A first wave of experimental closures around six schools have focused on closing approach and access roads. This is a useful step to building local consensus and community support. Given the challenges stated earlier, this programme needs to be rolled out to as many primary schools as possible, not only closing access roads, but filtering access on approach roads, and rerouting through traffic. This has to apply to main as well as residential roads, and the only way to do this is to start to design lower vehicle volumes across school neighbourhoods. Given the challenges for schools to open safely in the autumn with social distancing measures in place, and the clear links between air quality and children’s health, this is the right area for action, and has to be accelerated at pace.

The second area is more space for pedestrians, through pavement widening, mainly as a way to give people more space and to practice safe social distancing near shops and neighbourhood centres. Fixed barriers have been used as trials, placed mainly in parking bays. This intervention as way to make more space for pedestrians has its limits as barriers restrict filtered access, can be moved around, and have been misunderstood as part of road works.

The broader ambition to create more pedestrian friendly space is the right one, and the next steps to achieving this is to permanently filter and reallocate road space near residential shops, using more attractive planters, surface changes and filtered access. The case needs to be restated that the ‘pedestrian pound’ can bring in much more revenue to local businesses than those from offering car parking near shops. This is going to be a key area in any COVID recovery, as millions of people continue to homework and look towards their local neighbourhood to meet their daily needs. Indeed as the focus shifts away from city centres, neighbourhood shops are likely to see increased footfall. Creating pleasant car free zones that are around these shops that are well networked in to active travel and public transport will be key to their future vitality.

The third area is increased cycle lanes, using trial infrastructure such as orca wands, cones and even paint to quickly protect or further establish cycle lanes. Leeds has committed to 100km of lanes as part of emergency measures, with an ambition of 800km. These are large numbers, but have to be put into the context of a very large metropolitan district of 550km2. The use of emergency infrastructure should only be trials and transition to permenant infrastructure as sson as possible. Early trials highlight areas for improvement in existing cycle provision, in terms of width and continuity. The significant challenge ahead is to establish continuous cycle lanes on difficult and narrow routes that meet width requirements and are continuous without breaks. This will mean reallocating road space from motorised vehicles to cycles and pedestrians.

Reallocating road space may be the single biggest challenge in terms of a transition to the active travel city. It raises the long standing tensions between those who drive cars and those who ride bikes, further fuelled by historic poor design, competition over road space as well as the sensationalist media keen to draw fictitious battle lines between motorists and cyclists. Critical mass is key, laying down as many coherent routes as quickly as possible.

Rather than just strategic corridors to city centres, connectors and dense local cycle networks will start to crerate liveable neighbourhoods. One easy win is to re-mark neighbourhood road layouts to prioritise active travel, creating two way directional flows for bikes with single flows for vehicles. The ultimate aim is not to idolise cycling and walking, but to unlock its potential to offer the easiest, safest, quickest and cheapest options for short journeys.

The final, and perhaps most exciting area is Active Travel, or low traffic, neighbourhoods — closing and filtering residential streets to create safer home zones and more opportunities for walking and cycling. These trials take forward older home zone scheme ideas, and are also called mini-Holland neighbourhoods. A number are planned in Leeds communities, and there are advanced examples such as Waltham Forest. While these measures can bring benefits, given the lock-in to car dependency they can also generate early resistance and misunderstanding. Many people would agree to their benefits (less noise, less pollution, safe streets), but are less willing to accept changes that affect them in the short term.

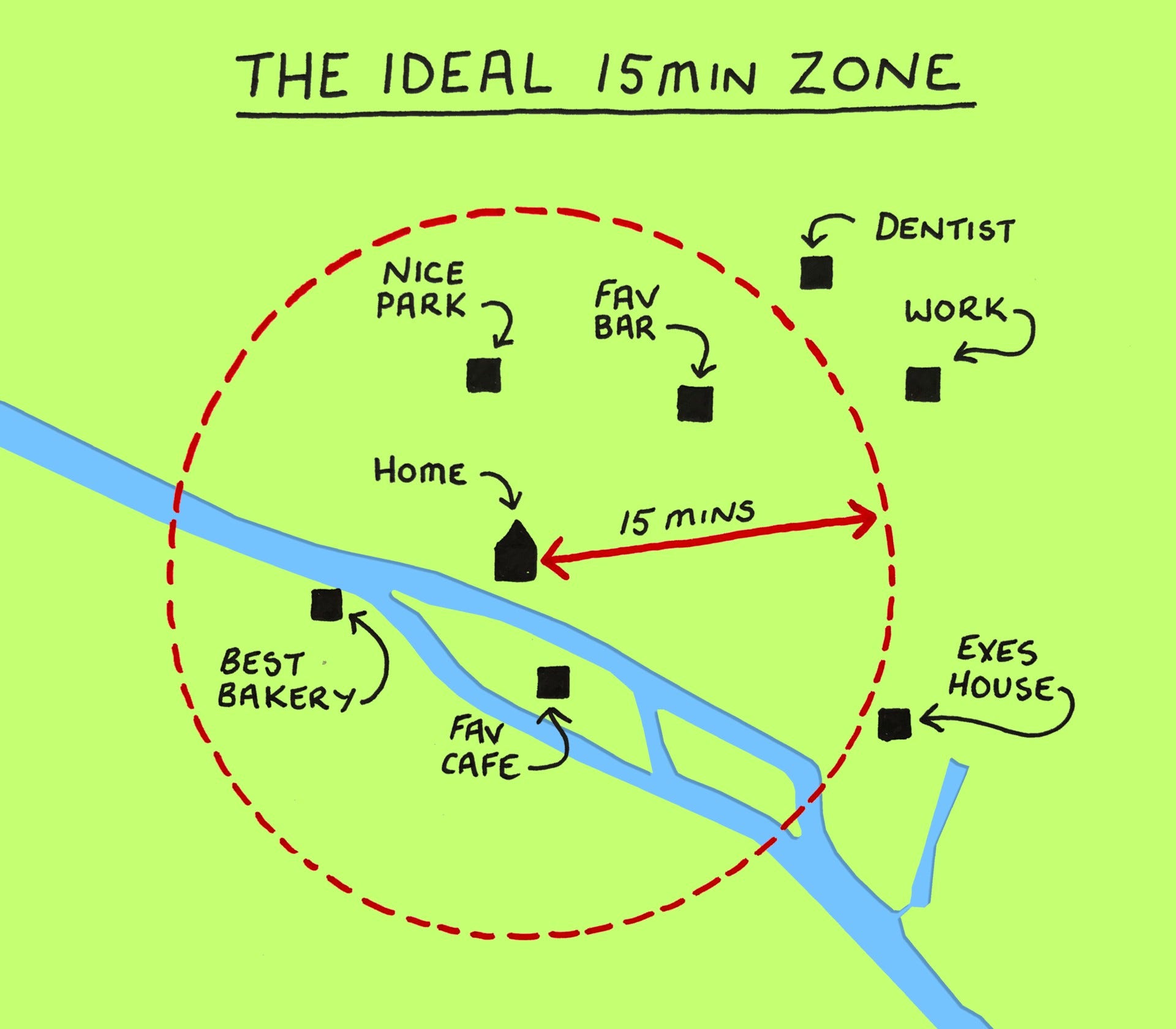

Geographically, these active travel neighbourhoods have to be large enough to make sense, include a critical mass of local goods and services, all areas between distributor roads, and significantly push out through-traffic. This brings us to the 15 minute neighbourhood idea, pioneered by Paris, where the city is divided into districts in which local goods and services needed for daily life can be reached within 15 minutes on foot, bike or wheelchair, with filtered access for those with mobility or emergency needs.

How these neighbourhoods fit together within the city is key. Without lower car volumes overall within an urban location, active travel neighbourhoods can become gentrified bubbles building on established advantages of higher income groups. Many people will continue to live near major distributor roads, outside the benefits of active travel areas. Active travel neighbourhood planning also has to go hand in hand with creating the right density of local goods and services, and creating connecting routes between them so they don’t become disconnected islands. This will mean creating access points, crossings and filtering across major distributor routes, and ultimately reducing these. These trials need to be part of a broad plan to make every residential neighbourhood in a city or town an active travel neighbourhood. Otherwise the city will fragment into those with heavier and lighter car volumes.

Tips for the rocky road to the active travel city

There are some broader lessons for those involved in steering the transition from motorway city to active travel city.

First, the issue of consultation. Given the speed of emergency and trial infrastructure, doing broad and detailed consultation is difficult, and there will be backlashes. The key point here is to continue to put out clear messages about the medium term benefits, and stick to these. Given the entrenched nature of car culture, car advertising and a well organised motor lobby, hearts and minds will not be won overnight. Alternatives to the car have been so impoverished that initially they seem deeply unpalatable. With the right level of investment this will change.

We need brave and visionary politicians willing to put themselves on the frontline and argue for why these changes are right – with civic, business, research and community groups prepared to back them and make it happen. Coproducing solutions will also create buy in and understanding benefits. Such sudden shifts are difficult and disruptive. But this is an emergency, and the benefits will outweigh the problems stored up in the transport system. Working examples of changes will start to become the living evidence of the benefits. The key question to frame community engagement is — what can we all do given the challenges we face? This is about community education, and, as Extinction Rebellion would say, telling the truth.

The second issue is an ability and desire to rethink the whole travel network. This is a leap from where many highways engineers operate who traditionally design roads to maximise the flow of vehicles. To design the active travel city, the task goes beyond ‘highways engineering’, where road design comes first and other aspects such as local services, greenspaces and housing are secondary. The priority needs to be flipped. Neighbourhood design that maximises wellbeing and prosperity comes first, and an integral part of that is a public and active travel system that makes it work.

Separating vehicle flows from active travel neighbourhoods is central, through for example limiting, redirecting and making traffic flows one way in residential neighbourhoods, freeing up space for active travel. Ultimately, cities have to pursue a ‘replacement’ rather than ‘additional’ strategy. City space is a limited commodity and there simply isn’t room for everything. It either services motor vehicles or active travel/public transport.

Third, the broader point is that there needs to be a vision of an active travel and car-lite city, otherwise interventions will be localised set pieces that don’t build towards that vision. Creating an active travel city ultimately means less cars circulating. We might need up to 60% less vehicle volumes to avoid dangerous levels of global heating. That also means not planning for electric cars replacing the internal combustion engine in the same numbers. A key part of vehicle constraint is creating a planning system which stops loading urban areas with more car-dependent activities, be they arterial retail parks, volume housing estates, relief roads or suburban leisure.

Fourth, without safer roads and lower vehicle speeds, it is also less likely that there will be a continued uptake in active travel. This last point is key. Beyond 20mph limits on residential streets, much more effort is needed to slow down vehicles. Committing to Vision Zero, eliminating all road deaths and casualties is the first step. It is now well established that even small decreases in speeds have a significant effect on road deaths. Designating many more roads as 20mph will play a part here as will quietways and reducing speed limits on non urban roads. This will also help to create connected and safer walking and cycling routes out of built up urban areas.

Finally, key to making all this happen is creating a sustainable and active travel team who know where they are heading, own an ambitious vision and have the power to make it real. This will involve replacing traditional highways departments with a Sustainable and Active Travel Department which is placed at the top tier of decision making in the Chief Executive’s or Mayor’s office where it and can directly influence planning, asset management and city development. A key part of this vision will be to tackle transport poverty, and to make active travel options work for everyone, especially keyworkers, and disconnected, low income communities.

There is a mountain to climb; but much has already been done and there is new impetus. Yet, a city cannot do this on their own. More direct policy guidance and resources are needed from central and regional governments. The current £27 billion road building budget needs shifting wholesale to walking, cycling and public transport. An active travel city needs to be part of a new bold national spatial plan, led by a newly formed Department for Sustainable and Active Travel that replaces the current DfT.

Multi billion investments in rapid transit, bus re-regulation and integrated ticketing, as well as revenues from congestion charging and a workplace parking levy, are essential to get cities and towns off the starting blocks and replace vehicle journeys and reduce volumes. Without these foundations it will be difficult to unleash the potential of walking and cycling. Given the evidence base for active travel, it is a surefire way to support a green and equitable COVID recovery and build in resilience to the challenges ahead, be they climate, social, public health or financial.

The active travel city is an opportunity policy makers, politicians and civic groups can grasp. While many are clearly doing their best, as Greta Thunberg reminds us, our best is no longer good enough given the scale of the challenges we face. We will have to do the impossible. Our ‘transport impossible’ is to rapidly replace, with care and dialogue, the motorway city with the active travel city. Through bold action, we will all start to reap the benefits in the coming years. But the bigger prize is to lay down a healthier, affordable and safe transport future for the next generation. We have to think big, and start now. If not us, then who? If not now, then when?