Monika Büscher and Nicola Spurling

Social change is critical to rapid decarbonisation. Citizens’ active participation in energy management is ‘as critical as technology’ for sustainability[1]; not least because social innovation could support decarbonisation at scale, and faster than technical or infrastructural innovation[2]. However, technocratic conceptions of social acceptance and societal readiness are misdirected. Innovation cannot succeed by demanding that individuals and society change to accept it.

Decarbon8 develops a new framework to evaluate the societal readiness of socio-technical innovations. This working note motivates this move in outline, provides working definitions of social acceptance and societal readiness from a socio-technical perspective, a sketch of the Societal Readiness Levels (SRL) framework for evaluation we are developing, and a set of questions that research teams can use to develop the societal readiness of their innovations.

Why take a socio-technical approach to social acceptability and societal readiness?

At a time when millions of people across the globe are demanding action on climate change, and 88% of UK citizens understand that human action is mainly or partly responsible for climate change[3], it can hardly be said that society is not ready for change. However, our innovations often do not enable change. People are imprisoned by mobility systems that leave them very little real choice over how to travel[4]. Indeed, the depth of systemic lock-in and the demand for social acceptance of narrow technological fixes (electric vehicles) and policy interventions (carbon taxes) delay action towards systemic and structural change[5]. We are headed for failure if we continue to design technologies, policies, infrastructures, ideologies that people cannot integrate into their everyday lives. The social acceptability of our solutions must improve. Methodologies that allow citizens genuine participation in innovation processes are needed[6]. A socio-technical approach can enhance the ambition and effectiveness of innovations by inspiring socially acceptable design for systemic change and societal transformation.

What is social acceptance in a socio-technical definition?

The social science is in: the ABC of transition theories, which all too often posit that education, nudging, or enforcement can effect social acceptance, is wrong[7]. A change of A – individuals’ Attitudes, will not automatically translate into B – Behaviour change, and ultimately C – Change in the system. Technocratic concepts equate social acceptance with behaviour change, evaluating the willingness of individuals to ‘take’ the technologies, policies, infrastructure innovations that experts devise. This hubris denies that there are factors that make technologies, policies, infrastructures more or less acceptable for people – they may not be desirable, useable or effective for good reasons.

A socio-technical definition of social acceptance helps us understand these reasons. It sees acceptance as a process by which innovation becomes embedded in everyday practices, that needs to be supported by good design and creative, inclusive design methods. It enables a focus on enhancing the acceptability of solutions. This may imply careful attention to useability, and the context of appropriation, it may require wider systemic change, it will often depend on stakeholder value chain mapping, and methods of collaborative design and responsible research and innovation.

What is societal readiness in a socio-technical definition?

Societal readiness refers to the readiness of a socio-technical assemblage to be acceptable to society. That is, it evaluates how well a solution supports appropriation at scale and at speed, as well as how it contributes to the public good. For example, a fully digitised on-demand transport solution may be highly practical and fit for appropriation. However, it may introduce societally unacceptable levels of surveillance. As a result, it has low societal readiness. Its societal readiness can be improved by building privacy preserving techniques into its use of data and by involving citizens and stakeholders in an iterative design process that discloses and addresses emerging unintended consequences through creative ethical and social impact assessment and design. To give a second example, a solution may be highly acceptable to affluent citizens with high mobility capital, but create mobility injustice for others. By anticipating and addressing issues of equity, gender, age, class, ethnicity and other aspects of inequality, innovations can be enhanced.

What is the role of place in societal readiness?

Technocratic approaches are often based on an approach to innovation in which ‘solutions’ are developed for imagined, generic users, in non-specific places. If people or places do not share the vision, they are seen as the problem.

In DecarboN8 we disagree with this point of view.

DecarboN8’s place-based approach addresses challenges faced across the North as specific, and very diverse places are seeking to rapidly decarbonise transport. Understanding place is an essential starting point for making decarbonised transport futures.

A key question is: How can we ensure that innovations in decarbonised travel are ready for specific places? This requires taking account of place-specific characteristics including:

- existing transport infrastructures and services that vary by place – this variety of starting points should feature in future designs;

- populations vary by age, disability, gender, ethnicity with different implications for inclusivity and access;

- different place-specific systems and cultures of mobility mean that lifestyles need to change in different ways;

- the end uses underpinning travel demands have different profiles across the region.

DecarboN8’s place-based approach emphasises that innovation must be designed and combined in ways that are more attuned to how people wish to, and are able to, practice transformation in different places.

Societal Readiness Levels (SRL)

There is currently a surge of interest in societal readiness, and various definitions of ‘societal readiness levels’ are emerging. The SRL concept originates in debates about a transition towards low carbon futures2 and the Danish Innovation Fund’s attempt to find a ‘way of assessing the level of societal adaptation of … innovation to be integrated into society’[8]. This contrasts with the more common approach of technology readiness levels[9], which evaluates how ‘proposed solution(s)’ meet ‘plans for societal adaptation’. For example, in the context of future transport, a technology readiness approach would evaluate the decarbonising potential of a proposed innovation, and place responsibility for increasing society’s readiness for it with individuals, communities, societies, politicians, and policy makers. It would propose innovations and then ask how to alter people’s attitudes and behaviours to effect change.

DecarboN8 is critical of this technology readiness approach.

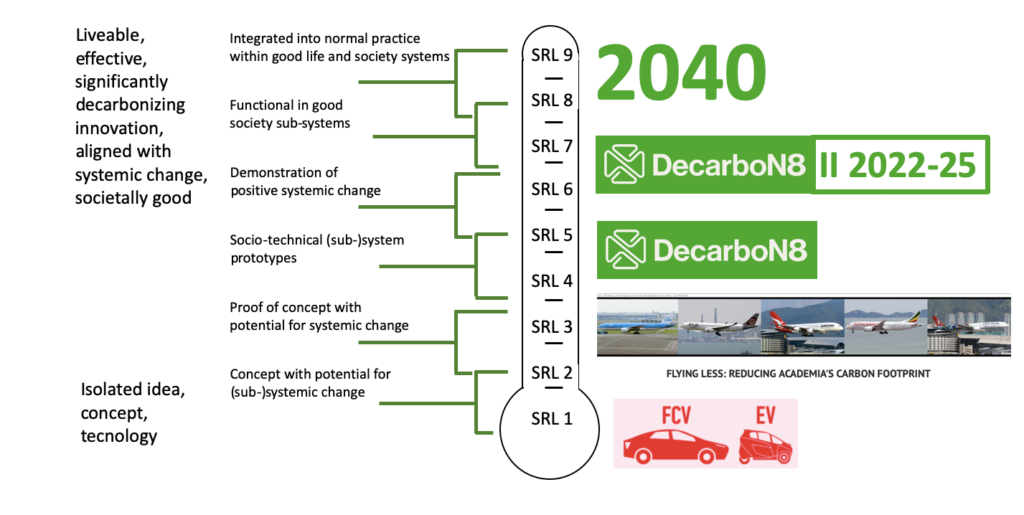

The societal readiness levels that we are developing (see figure 1) turns the tables. Instead of asking how society can be made ready for innovations, we ask: How ready are our socio-technical innovations for society?

At the lower levels in our emerging socio-technical framework of societal readiness levels, are concepts and technologies like electric vehicles, which have the potential to support systemic change but are isolated from real world practice and lacking societal and material infrastructure for large-scale appropriation. Moving up the scale are experimental embeddings of technologies, such as the Tyndall Travel Strategy and the University of Edinburgh’s business travel reporting tool prototype, which are being effectively used to reduce emissions from academic travel, and are engendering social innovations, such as no-fly academic conferences. Within its 2019-2022 remit, the DecarboN8 Network aims to reach innovations that are at SRL4 and 5. Plans for future efforts envisage achievement of SRL 8 and 9, with liveable, effective, significantly decarbonising innovations (net zero carbon), which are aligned with systemic changes and evaluated as societally ‘good’ by a broad and diverse group of stakeholders, including citizens.

Achievement of high Societal Readiness Levels depends upon engagement with diverse stakeholders and translation of insight into synchronised technical, regulatory, policy, and social innovation. Discussion of ‘Impact Readiness Levels’[10] by the Dandelion project on an inclusive, innovative and reflective societies-sensitive valorisation concept offer valuable insight into the kinds of engagements with stakeholders that are conducive to our aims.

How to design for societal readiness?

The DecarboN8 network seeks to facilitate co-creation of a socio-technical framework for achieving high-quality innovation for rapid decarbonisation of transport in the UK. The discussion in this document is intended as an invitation to members of the network to engage critically with the notions of social acceptance and societal readiness, and co-create a good framework with us.

Below we raise some questions that we believe can support designing for socio-technical societal readiness. They are by no means exhaustive or prescriptive:

- Is your innovation (technology / policy / infrastructure / transport plan / form of activism) ready for the individuals, communities in our society?

- Is your innovation good for society? Now and in future? How do you know? What are the contextual and systemic dimensions of your innovation?

- Have you considered all relevant perspectives? Who has been involved in your design process and how? Have all those affected had a say? Have they been listened to? Have you made it possible for the less powerful to be heard on an equal footing?

- Have people had an opportunity to try out your innovation in their everyday lives? Have you undertaken multiple iterations of your design to discover disruptive consequences?

- Have you considered and addressed ethical issues, from accessibility to mobility justice to datafication? From individual to societal scales? Now and future generations?

[1] EU Commission(2012) Energy roadmap 2050. Publications Office of the European Union.ISBN 978-92-79-21798-2, doi:10.2833/10759.

[2] Allwood, J. M., Gutowski, T. G., Serrenho, A. C., Skelton, A. C. H., & Worrell, E. (2017, June 13). Industry 1.61803: The transition to an industry with reduced material demand fit for a low carbon future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. Royal Society. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2016.0361

[3] YouGov – International Climate Change Survey, Fieldwork: 11 June – 22 July 2019

[4] Anthony Rae, 25th November DecarboN8 Launch, Leeds Crowne Plaza Hotel; Urry, J. (2004). The ‘System’ of Automobility. Theory, Culture & Society, 21(4–5), 25–39.

[5] UNEP (2019) United Nations Environment Programme. Emissions Gap Report 2019. UNEP, Nairobi. P. 54

[6] Cardullo, P., & Kitchin, R. (2019). Being a ‘citizen’ in the smart city: up and down the scaffold of smart citizen participation in Dublin, Ireland. GeoJournal, 84(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-018-9845-8

[7] Shove, E. (2010). Beyond the ABC: climate change policy and theories of social change. Environment and Planning A, 42(6), 1273 – 1285.

[8] Danish Innovation Fund, 2019, https://innovationsfonden.dk/sites/default/files/2019-03/societal_readiness_levels_-_srl.pdf; Schraudner, Martina, Fabian Schroth, Malte Juetting, Simone Kaiser, Jeremy Millard, and Shenja van der Graaf. 2018. ‘Social Innovation The Potential for Technology Development, RTOs and Industry. Policy Paper’. Fraunhofer. http://www.thertoinnovationsummit.eu/en/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/20181220_RTO-Innovation-Summit_Policy-Paper-1.pdf.

[9] Mankins, John C. 1995. ‘Technology Readiness Levels. White Paper’. NASA. https://aiaa.kavi.com/apps/group_public/download.php/2212/TRLs_MankinsPaper_1995.pdf.

[10] Dandelion Project. (2018). IIRS Valorisation Methodology. http://www.dandelion-europe.eu/en/infobase/iirs-valorisation-methodology-/iirs-valorisation-methodology-1.html