by Greg Marsden

Drive Less? Who? Me?

As local and national transport authorities work through the task of what decarbonising transport in line with the UK’s commitments really means we come to one inescapable truth. It means travelling less by car. Transport Scotland has written it down as a 20% reduction in kilometres travelled by 2032. Many local authorities are going even further. Even the Department for Transport, which has been built around decades of projecting traffic growth suggests that an overall stabilisation or reduction will be necessary. It is now well understood (although not generally foregrounded by politicians) that electrification of vehicles alone will not get emissions down far enough, fast enough.

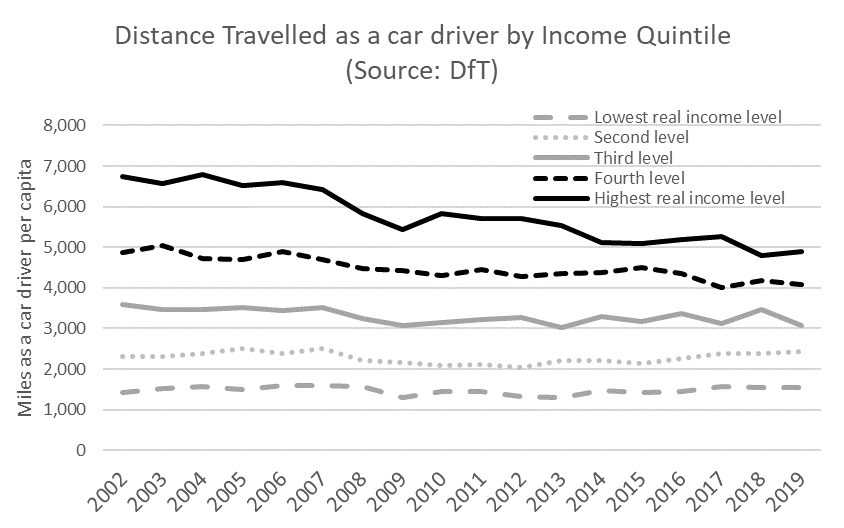

So, to driving less. The trumpets sound and the war on the motorist begins, right? Wrong. If we think about this differently. First, it is important to know that the distance travelled as a car driver per person has fallen in the UK by 496 miles to 3198 miles (13%) per person per year over the period 2002 to 2019. This has happened without, I would argue, any significant policy to bring that about. It has fallen most for the most well off as shown in the chart below. So, we shouldn’t presume that a decline in driving is somehow impossible to align with people’s preferences, unachievable or that it will be unfair on those who have to travel.

One of the reasons appeals to “drive less” are both challenging and challenged is that people have constructed their lives around a certain set of assumptions and it is difficult to unwind commitments in the short run. And that is the key here – not to think about this just in weeks but to look at the next six months or couple of years.

Life course and travel behaviour

There is a strand of research in transport which has been looking at travel behaviour over the life course, led by Martin Lanzendorf and, in the UK, Kiron Chatterjee at the University of West of England. The latest thinking on this was shared at the recent DecarboN8 conference (and you can watch that back here) but basically it says that people are more likely to make bigger decisions on mode use when their life circumstances change – e.g. a change of job or housing location, having children or having children move out, taking on caring responsibilities etc. On average, people living in private rented accommodation move every four years and in owner-occupied housing every ten years. Around one third of people move or lose a job in a given year.

People take on cars and give them up throughout their lives and so the idea of someone being a ‘car owner’ is a gross simplification. One way of reducing car use is to recognise that there are some times in some people’s lives when vehicles are more necessary but to delay when that starts and to accelerate the possibility for people to give up cars or reduce their ownership once those constraints are released.

In a working lifetime, for example, one might be travelling for 40 years. If people use the car for 30 of those years then a 20% reduction could be achieved if we can squeeze this to 24 years. Very few people commute by car every day of their life so doing things differently is possible. If the car is not in use most days for the commute then it may prompt a decision to get rid of it altogether. This in turn will discourage use for a range of other trips which only make sense because the car is sat there anyway.

Car ownership and life changes: My story

I reflect on these possibilities with my car owning life history from my time as a PhD student in 1994. As you read my life story, think about your own – and in particular the importance of specific needs and journey purposes in triggering decisions on entering and leaving car ownership and car journey routines.

The first car

I was able to walk or cycle to the University of Nottingham throughout my three years there, biking up to 25 minutes by my final year. On moving to Southampton in 1997 I took on a small diesel. My commute was a 10-minute walk but a long-distance relationship led to the purchase. From 1998 to 1999 we kept the car but then sold it as we left the country. In 2001 we again bought a car (a VW polo 1.0), not for my commute (which was now a train ride to London) but for accessing sport, to allow my partner to take on supply teaching work to supplement her PhD grant and so we could reach the New Forest for walks.

A new city and new circumstances – two cars

In 2003 we moved to Leeds and had our first child. Our housing location decision was tricky as we had to guess where my partner would find a job. However, we located close to a bus service so I did not have to drive. We did however take on a bigger car. Come 2004 however, my partner’s commute to York and the inability to find sufficiently local childcare meant we moved to two cars (a 1.0 litre and a Berlingo van) and both drove to work. In 2006 our second child was born and life was beginning to get even busier.

One commute but hectic schedules – two cars

Whilst we switched cars a bit, we retained two and the next shift came in 2011 when we moved to York so that my partner could have a cycle commute and I was then the only commute driver. I experimented for four months with a bike-bus-walk round trip but at nearly two hours door to door versus 45 minutes in the car it was a practical no-brainer. The second car was also kept for a variety of after-school activities which were in all sorts of places (and my commute car was a Kia Picanto with the boot capacity of 3 shopping bags so not ideal for the cello or a weekend away). I also took on a management role which required me to be in Leeds four days a week – so a heavy commute from my perspective (52 miles round trip). I grew to dislike the A64.

Thinking about change and then two cars become one

In 2016 I stepped down from my management role and reduced my commute to two days a week – I am lucky to have had that flexibility. We still had lots of scheduling clashes, and two cars were convenient for sure, but I’d never wanted two and was looking for a way to cut back.

Wind forward to spring 2020 and Covid-19 and our cars sat pretty much idle on the drive for nearly 18 months. Then, my eldest child went to University and suddenly the time clashes which had been a feature of our pre-Covid lives were never going to come back. The brakes on the little car needed £600 of work doing on them and so we have sold up and switched to one car (an EV).

I commute irregularly on the fantastic York to Leeds City Zap bus service. Whilst the door-to-door trip is 90 minutes; I would say it now compares favourably as I can work for around 30 of those. It certainly works as an occasional commute. Having one car will take a bit of getting used to but it is hard to see us looking back. A new Enterprise Car Club vehicle should be appearing soon within a 12-minute bike ride from the house for times when we really need that flexibility.

Rethinking car ownership and use

So, I am a car owner but that is not one uniform thing. Those of you who have ever owned a car will be able to write your own list of such different decision-points. There have been lots of opportunities to re-evaluate our ownership and use decisions, and we have. Not all of them have resulted in less ownership or use, indeed, some have inevitably gone the other way.

However, the scope for reducing car use by integrating behaviour change with life-course events is significant and real. It is something that everyone can engage with. We can delay the move to owning a car. If we take on more than one car then we can reduce the period we do that for. Where we move to places where car access without ownership is possible and there is a strong complimentary mobility offer then we can think about zero car ownership. No-one is born a car driver and there is agency in our decisions.

Policy changes can help

If travelling less is essential, then we also need to rethink our relationship with the car. Policy changes that could support that include:

- rethinking why we provide company car tax benefits

- adjusting residential parking permit policies

- mandate incentives around house moves or job moves which support giving up or reducing car ownership

- investing in facilities to create 15-minute neighbourhoods so that more of the things we need in everyday life are accessible by bike, walk or wheel.

We can tackle car ownership and use in many different ways without seeking to demonise it. This kind of people and lifestyles focused approach remains strangely absent from the Government’s Transport Decarbonisation Plan and that needs to change urgently.