by Daniela Paddeu

The trouble with same day delivery and free returns

How do you imagine the future? The United Nations say that 68% of worldwide population will live in urban areas by 2050. That’s an additional 2.5 billion people living, moving and demanding products and services in urban areas. This will have a positive impact on the economy vitality of urban areas, but will also significantly contribute to traffic congestion, reduce road safety and worsen air quality, with related negative implications on climate and public health. A post-pandemic world suggests people commute less, as more people work from home, and this might let us think that there is a smaller number of vehicles on our roads. However, this might not be true. The UK is the first market in Europe for e-commerce, and the third in the world, just after China and the U.S. Buying is easy: you can buy whatever you want, have it delivered on the same or the next day, sometimes even the same hour, and you can also return it if you don’t like it. It’s easy! Consumers buy much more than they need, and 25% of products are returned. This generates an increased volume of van movements (+106% increase in the last 25 years), and numbers are expected to significantly grow in the future.

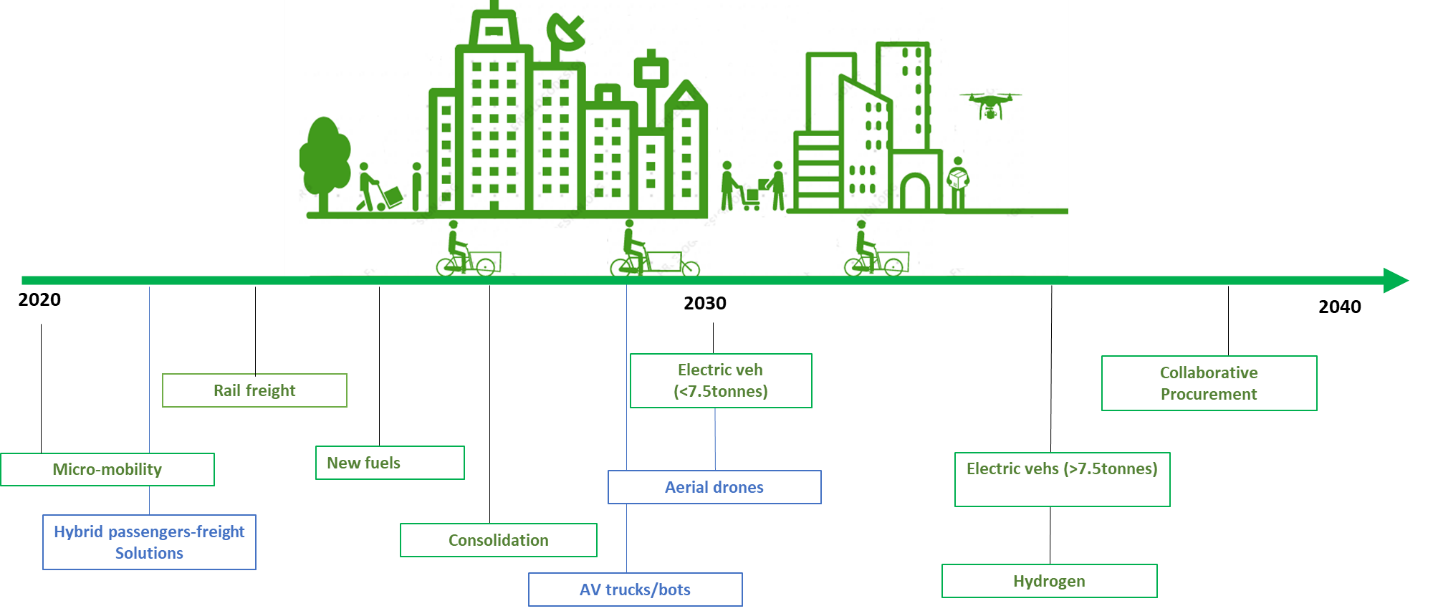

Therefore, it is urgent to design and undertake actions to reduce the negative impact of last-mile deliveries. This was the main driver of the CoDe ZERO project. The project explored stakeholders’ perspective towards sustainable solutions to decarbonise urban freight, focussing on the North of England. Together with key freight stakeholders based in the North, we co-designed a roadmap with a series of solutions that can be implemented in the next 20 years to reduce carbon emissions from freight movements in urban areas.

Technology vs behaviour change

Findings show that stakeholders understand the importance of decarbonising urban freight to achieve the net zero target by 2050 (or even sooner). They also foresee challenges, mainly related to the development of efficient cleaner technological solutions and to behaviour/organisational change. They believe that there will not be a single perfect solution. Instead, urban freight decarbonisation will require the integration of a series of technical solutions and organisational/behavioural change.

Among the technical solutions, electrification and new fuels (e.g., hydrogen) are seen as the most promising ways to achieve urban freight decarbonisation. However, their full implementation might require time, especially due to technological development, and other solutions would be needed to start reducing carbon emissions in the short term. These include, for example, the use of cleaner fuels (e.g., biogases), urban freight consolidation schemes, and the use of e-cargo bikes together with micro-consolidation. However, there might be some big challenges to implement these solutions, and a lot of uncertainty towards their effectiveness. For example, big logistics operators already consolidate at a very optimal level. So, are we sure this is going to be a commercially/operationally viable option? Also, electric might not be the only net zero solution for an urban environment. Can Compressed Natural Gas or Liquefied Natural Gas have a role given the goal is net zero not absolute zero? Consolidation schemes, and collaborative schemes in general, were identified as being equally “powerful” compared to more technological solutions. However, bigger companies might be in a stronger position in terms of managing and sharing information and operations. So, what if some players gain a greater advantage than others, and smaller operators are not strong enough to survive?

What’s different about the North?

The North is very varied in density and topography and includes conurbation patterns, with a number of bigger urban centres (e.g., Manchester, Liverpool, Sheffield, Leeds), and national parks. This characteristic might be key in supporting modal shift from road to rail, with rapid rail freight systems among the major centres that would act as a macro-urban system. However, this might rely on investments in the rail infrastructure, and in any case, it would still require an additional solution for the very last mile of the chain.

In addition, the specific policy structure of the North might lead to an inconsistent application of policies between localities, generating regional variations for urban freight decarbonisation depending on local authority priorities.

In general, the findings of the project indicate that there might be a range of solutions to decarbonise urban freight, but it is not clear how these solutions should be practically adopted, and where responsibilities lie. Considering future policy and research, a strong final question about urban freight decarbonisation remains: how do we get there?