by Greg Marsden and Richard Walker

This post originally appeared on Policy Leeds

Previously in this blog series for COP26, Paul Chatterton laid down the challenge for urban policy makers to “act like it’s an emergency” in their response to the IPCC’s call for “immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions”. Here Richard Walker and Professor Greg Marsden set out the urgency for UK transport policy, and offer principles and solutions for rapid transport decarbonisation.

DecarboN8 is now two years into its mission, as an EPSRC-funded network, to bring together academia, business, government and civil society across the North of England to address transport decarbonisation. Everybody brought together by DecarboN8, from elected representatives to transport professionals to private sector businesses to civil society organisations, has a deep and personal desire to do their bit and be part of decarbonising the UK. Going into COP26, we have developed the following key messages, divided into the urgent core problems we need to address, the principles that should be adopted in addressing them, and the solutions we recommend.

Problem: We are not going fast enough

The urgent core problem in transport decarbonisation is that we are not going fast enough.

There is a fixed amount of fossil fuel we can burn in the next 100 years or more without risking more than 1.5–2 degrees of global warming. The UK’s ‘Paris commitment’ is to act to ensure that this level of global warming is not exceeded. Depending on how you define the UK’s ‘fair share’ of the global fixed budget, at present rates of consumption, we will burn through that budget in the next 8–15 years.

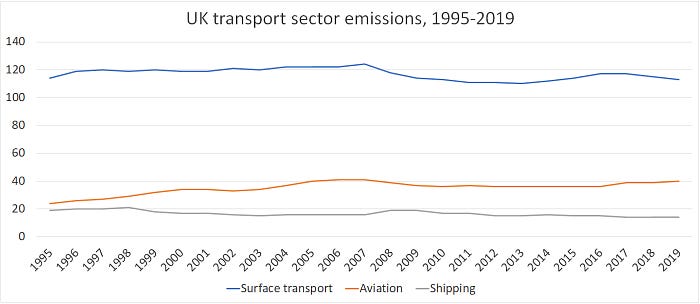

Where does transport fit in? Sadly, the UK transport sector has essentially wasted the 26 years that the COP process has been in existence. According to the UK Climate Change Committee’s figures, since COP-1 in Berlin in 1995, UK surface transport emissions had fallen by less than 1% by 2019. Meanwhile UK aviation rose by two thirds. Counting the UK’s share of shipping as well, the CCC data shows UK transport sector emissions have risen from 157 MTCO2e in 1995 to 167 MTCO2e in 2019. Transport has climbed from one fifth of total UK greenhouse gas emissions to one third.

Too great a share of recent improvements in engine efficiency have been ploughed back into bigger and heavier vehicles such as SUVs, or growing the number of jet aircraft flights taken, rather than into lower emissions.

Problem: Technology transition is not enough on its own

Having spent 25 years burning through our fixed carbon budget, we have run out of time to rely solely on technology transition to deliver the transport emissions cuts we need. The only transport decarbonisation pathways that meet our Paris commitments require both a rapid technology transition to zero emission vehicles AND a major reduction in demand for fossil-fuel powered transport starting immediately, whilst we are waiting for the technology transition to feed through. This means a reduction in overall road traffic levels and therefore a major shift to public transport and active modes.

Our previous inaction also means that every different type of place — from crowded cities, to affluent suburbs, to idyllic rural villages — has to decarbonise, starting now. Every year of inaction makes the next more difficult. No type of place is ahead of the decarbonisation curve, and so no type of place can get a free pass to fall behind the curve, or to avoid the changes that decarbonisation will require.

Problem: The UK Net Zero Strategy spin plays down the action needed

Where does the UK Government stand on this? In transport, the publication of the UK Department for Transport’s first ever Transport Decarbonisation Plan (‘TDP’) in July 2021 was a big step forward, and it now comes under the wider umbrella of the Government’s overall Net Zero Strategy, published on 19 October 2021.

Both documents’ existence is a tribute to the Climate Change Act 2008, which put a legal framework around the carbon budget concept, and requires the Government to say how it will stay within the Climate Change Committee’s interpretation of our carbon budget.

First the good news: the TDP says many of the right things. For example, in it can be found the crucial acceptance that we are going to need to reduce our use of cars and aircraft during the 2020s, as well rapidly delivering a technology transition away from fossil fuel powered vehicles.

However, the TDP, like the Net Zero Strategy, tries to face both ways, and its spin is that no serious change to lifestyles of overconsumption is necessary. For example, in his foreword to the TDP the Secretary of State for Transport states “It’s not about stopping people doing things: it’s about doing things differently. We will still fly on holiday, but in more efficient aircraft, using sustainable fuel. We will still drive on improved roads, but increasingly in zero emission cars.”

If that approach was ever viable, it no longer is. As DecarboN8’s Kevin Anderson argues: “no non-radical futures are now available”. What is needed instead?

Principles we can adopt

Before we turn to solutions, it is worthwhile establishing some broader principles that we can adopt in facing and addressing the problem.

Principle: Tell the truth

The first one is fundamental: tell the truth. For example, it feels almost as if more effort has been expended in the past 25 years on trying to hide the contribution of international aviation to global warming than on trying to do something about it. Why? At root, because flying around is amazing and a pretty cool perk of being rich. But you can’t hide from physics. We can lie to each other, and to ourselves, as much as we like that we can delay tackling the issue of frequent flying, or that we can reach for measures such as offsetting instead, but you can’t lie to the atmosphere. So, time to stop.

Principle: Work with society

Democracy is famously the worst system of government apart from all the others, and it’s a good rule that there should be no erosion of democratic principles in addressing the climate emergency. But how to take the tough decisions transport decarbonisation requires? The key message from DecarboN8’s work on societal readiness is to revisit the ideal of ancient Athens and encourage participative and deliberative democracy. It turns out that citizens’ juries or citizens’ assemblies are quite capable of facing the facts, weighing difficult trade-offs and making tough decisions. The media — the fourth estate of a functioning democracy — can help, but it needs to start doing its job.

Principle: Make it fair

The third principle is fairness or equity, or what is widely called the just transition. In UK transport decarbonisation this means recognising that, as the Place-Based Carbon Calculator shows us, the transport carbon footprint of the richest communities is three or more times the size of that of the poorest communities. It’s the better off who need to do the most. The good news is that the better off have more resources and more opportunity than the worse off to change their transport behaviour. Indeed, during the Covid pandemic, many already have.

Solutions we can adopt

Here are some headlines on the measures we can adopt to deliver transport decarbonisation in a hurry.

Solution: Find quick wins

We have been given an unexpected head start on our transport decarbonisation journey as a consequence of the tragic Covid pandemic. Now is the time to ‘lock in’ long term some of the reductions in commuting and business travel that flowed from the rapid shift to Teams and Zoom. People like commuting less!

For the mobility demand which will necessarily and rightly remain, the ‘transport planning toolkit’ is full of tried and tested measures which can help.

Interesting examples among many include:

- Multi-modal mobility hubs, as developed in Bremen, where you can interchange between public transport and sustainable onward modes such as shared electric cars, e-scooters and e-bikes.

- Cheap public transport, such as Vienna’s €365 annual pass.

- Road space reallocation, taking street space from private cars and giving it to walking and cycling, trees and outdoor seating — as is being dramatically rolled out in Paris.

Solution: Stop making the problem bigger

We have to be planning for fewer cars and more shared cars. This means we don’t need more road capacity. The emphasis in road infrastructure development strategy should be on resilience: maintenance and adaptation, not new build; reallocation not expansion of road space.

Solution: Integrate technology, people and place

The revolution in information technology epitomised by the mobile phone app offers immense opportunities to facilitate mobility which convenient, flexible and fun to use. The longstanding transport planning toolkit can be updated to incorporate and make the most of these new opportunities.

Solution: Focus innovation outside of urban centres

In UK, the majority of transport carbon emissions arise in suburban and peri-urban places outside of the cities, where we have spent several decades building infrastructure and facilities based on private car mobility. As such, many such places now feel themselves to be car-dependent. Restoring locally-accessible facilities, innovations such as mobility hubs and demand-responsive transport, and behaviour change can offer practical decarbonisation paths for such real-life places and their people.

Solution: Coherent governance

We need coherent transport carbon governance: a framework for organising and monitoring transport decarbonisation at the national, regional and local levels that ensures that every local or regional area knows what decarbonisation it needs to deliver, and by when. The framework should ensure that no place is allowed to fall behind the overall transport decarbonisation pathway, unless others are racing ahead of it.

Decarbonising transport will require bringing everyone along for the ride

We have the principles and solutions to deliver rapid transport decarbonisation, but we also need to recognise that transport decarbonisation is not just a transport problem. Success will require joining up with other areas of government policy such as spatial development (housing, planning, economic development and industrial strategy), and health and education.

We must also recognise and work with all other actors in the economy and society, including business both large and small, social enterprise, charities and engaged citizens. People want to act and so many organisations can do things faster and better than government can do, given the right framework and incentives.

Decarbonising mobility needs to happen for the sake of the planet, but it can also be an opportunity to build better places to live and happier, healthier lives.